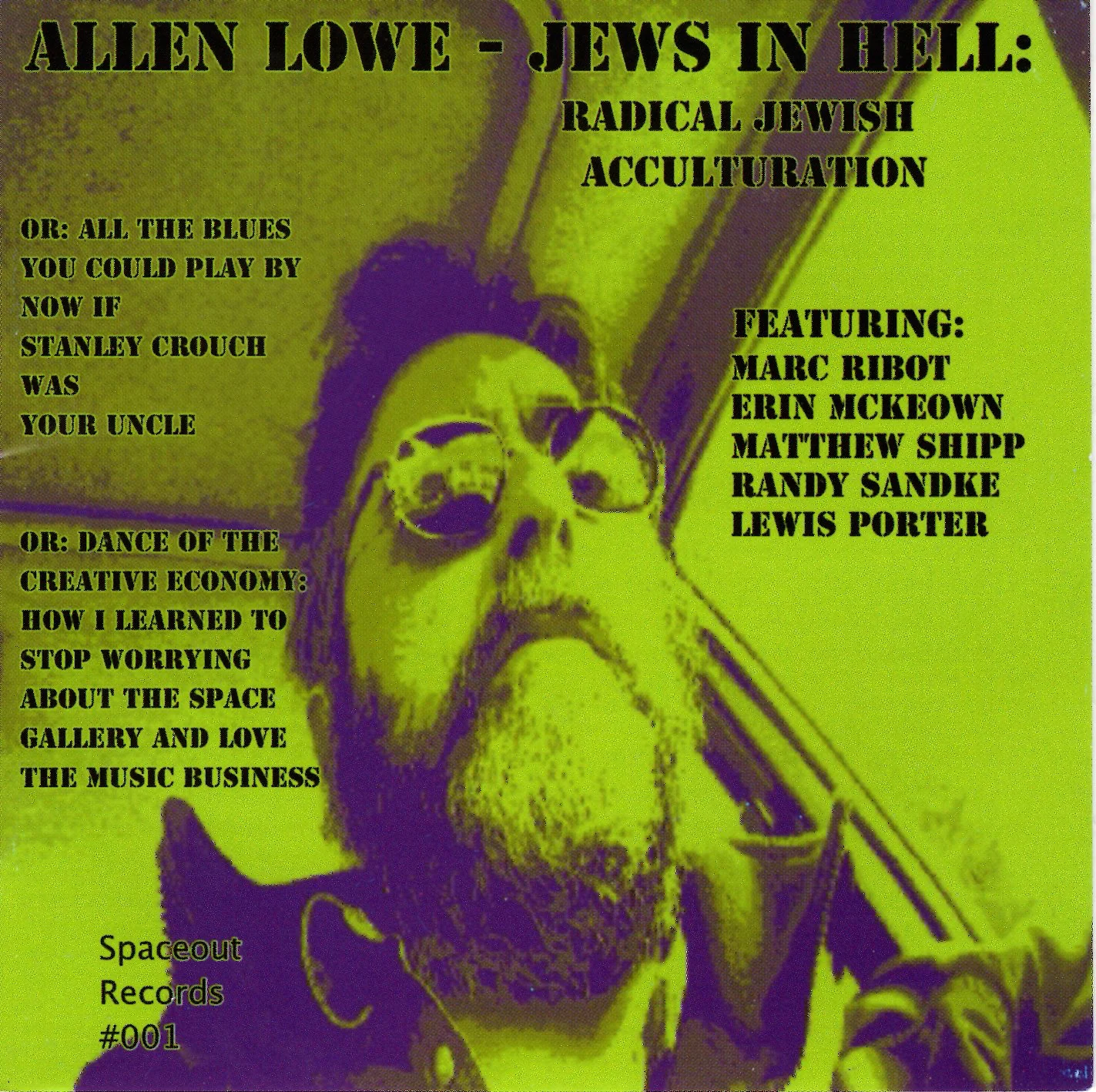

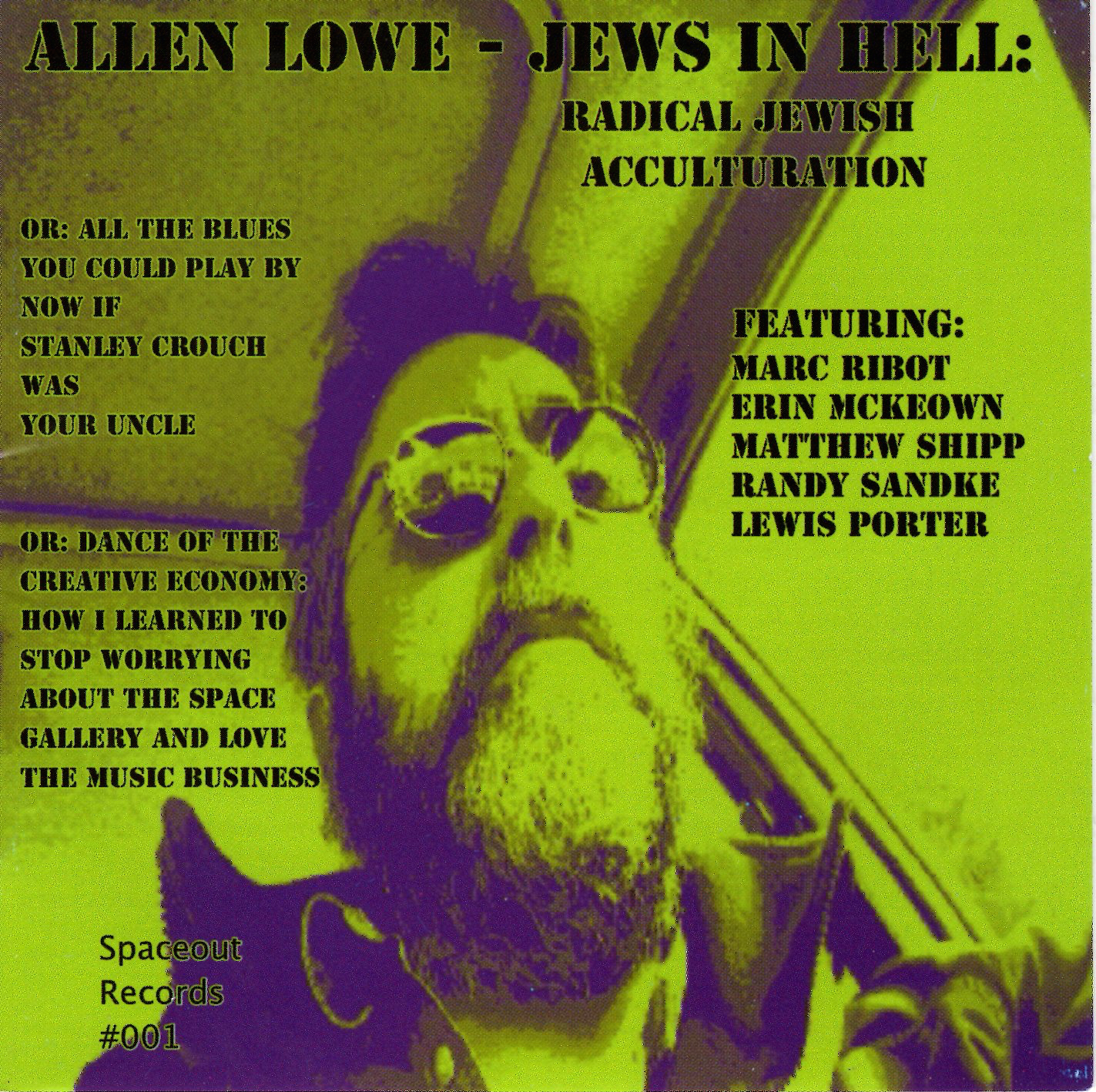

Jews in Hell: Radical Jewish Acculturation: Or: All the Blues You Could Play by Now if Stanley Crouch Was Your Uncle: Or: How I learned to Stop Worrying about the Space gallery and Love the Music Business

For this one you should really read the ridiculously long booklet of notes (which Tom Hull, who did not like the CDs, described as “the manual.”) This project was, in essence: ten years of the angry frustration of living in Maine, ten years of virtual friendlessness (which has by now extended to nearly 15), 10 years of almost not playing. I did, during this time, out of sheer boredom (maybe like one of those guys living in the Arctic under a climate-controlled dome; or like somebody trapped for years in a land without sun), pick up the guitar, retreat to my basement, and practice, practice, and practice some more, all the while becoming obsessed with tubes and amplifiers. I started writing songs and, though I first thought of trying to find a singer, I decided finally that it was easier to just sing them myself. I was becoming interested in punk rock and some other things, and wrote some folkie-type tunes (see Oi Deah‘, something based on Delmore Schwartz, a Lou Reed parody, a Jewish minstrel song based onJewish stereotypes, and a neo-Carter family mountain thing, which I got the wonderful Erin McKeown to sing. I also bought and started playing an alto sax, part of my new identity in what was beginning to amount to membership in the Musician Protection Program.

Yes, it’s true, in many ways this CD was intended as a big FUCK YOU to Maine, to its arts institutions (most particularly a pathetic little Portland room that has flailed around for some time attempting to book trendy indie rock and bad painters, and calls itself The Space Gallery). It was also, however, a way of addressing certain post-middle age ideas of ethnicity and creativity and pre-mortality (and, yes, a little dig at John Zorn: “mommy, why won’t that mean man return my emails? I’ll show him…”).

Most significantly this recording signaled the beginning of some work with the always-stimulating Marc Ribot (who did a few solo pieces), a collaboration with Matthew Shipp (whose playing simply overwhelmed me), Lewis Porter (one of the most intensely creative and inventive pianists in the business), not to mention a brief reunion with Randy Sandke, who suggested and brought along Scott Robinson; also, a brief musical dalliance with Erin McKeown, whose work I had encountered and admired on local alternative radio.

But, as I said, read the notes, which are included with the album.